José Luis Bazán, legal adviser to the Commission of Episcopal Conferences of the European Union (COMECE) in Brussels. / Credit: Victoria Cardiel/EWTN News

Vatican City, Oct 24, 2025 / 08:00 am (CNA).

The rise in violence and attacks against places of worship and believers, traditionally associated with regions of conflict, has seen a worrying upturn in recent years in Europe, South America, and North America.

According to the latest report from Aid to the Church in Need (ACN), in 2023, France recorded nearly 1,000 attacks on churches, and more than 600 acts of vandalism were documented in Greece.

Similar increases were observed in Spain, Italy, and the United States, where attacks not only target church property but also include disruptions of worship services and attacks on clergy.

“These attacks reflect a climate of ideological hostility toward religion,” said José Luis Bazán, one of the report’s authors, in a statement to ACI Prensa, CNA’s Spanish-language news partner.

For Bazán, the incidents are no longer just isolated episodes: “Attacks or acts of vandalism against places of worship are pandemic.”

Bazán focused on a phenomenon that crosses continents: “I’m talking basically about Europe and the Anglo-Saxon world — Canada, the United States, New Zealand, Australia — and, by extension, also Latin America, particularly the Southern Cone: Chile and Argentina.”

In Chile, he explained, approximately 300 attacks of vandalism against churches have been recorded, some linked to far-left groups and associated with times of social tension, with examples such as fires being set and attacks in the country’s south.

“We have fragmentary elements here and there, but if you put them all together, you realize the upward trend,” he said.

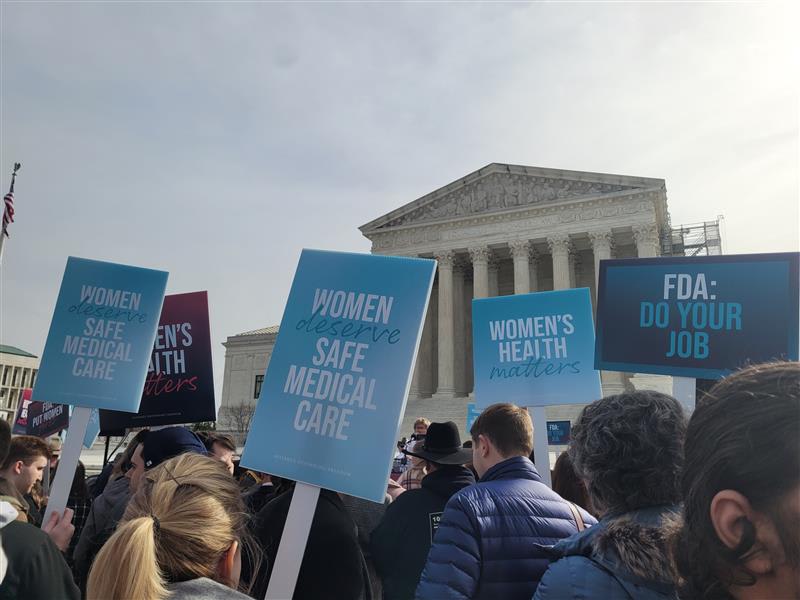

Bazán also mentioned coordinated episodes of vandalism on occasions such as International Women’s Day on March 8 in various Latin American and European countries. He noted that in Colombia, Peru, Chile, and Argentina, “there are radical feminist attacks against churches.”

“Sometimes what they do is vandalize them with slogans, as in Spain as well, like ‘Get your rosaries off our ovaries,’ or an even harsher one, which said something like ‘You will drink the blood of our abortions.’ They put this in front of the Logroño co-cathedral,” he lamented.

Bazán also mentioned the case of artist Abel Azcona, who “stole from churches, attended more than 200 Masses, and stole the consecrated hosts,” writing the word “pedophilia” on the ground with them.

“The case reached the European Court of Human Rights, which unfortunately doesn’t fully understand the meaning of consecrated hosts to Christians and thought it was simply an object like any other,” he explained.

The expert emphasized the seriousness of the fact that this judicial interpretation has given “room for desecration, and from now on, anyone can steal consecrated hosts.”

Most attacks go unpunished

Bazán, who is a legal adviser on religious freedom for COMECE (Commission of the Episcopal Conferences of the European Union), also decried the fact that most attacks go unpunished.

He noted that in the case of vandalism, “it is sometimes difficult to know who is doing it.”

“These are attacks that occur at night, in remote churches, without cameras,” pointing out just how vulnerable religious heritage is.

“We’re talking about tens of thousands of churches in Europe, many of them vulnerable and in areas with difficult access,” he explained, after noting that the large number of farflung churches, small shrines, and chapels in rural areas makes prevention and investigation difficult.

‘Soft persecution’

The ACN report also warns of growing pressure on freedom of conscience in Europe. To explain this, the expert echoed the definition given by Pope Francis: “He denounced this [soft] persecution. Basically, what’s happening is an attempt to hijack people’s consciences,” Bazán pointed out.

As he explained, this form of harassment “goes unnoticed, because in general, in the West, people can go to church, practice rituals, sacraments, and so on.” However, “the question is what also happens in social life.”

Freedom of conscience under pressure

The jurist offered concrete examples of these restrictions: “What happens, for example, in universities when there is a professor who defends a position in accordance with religious principles, or a doctor or nurse who decides not to perform an abortion and does not want to be, let’s say, subject to any victimization or sanction?” he explained, citing the example of Spain, where an attempt is being made to create a list of doctors who object to abortion, which would have practical consequences for their careers.

“They probably won’t be able to serve on the hospital’s ethics committee, they probably won’t ever be considered to head a department [of] for example gynecology. In other words, there are many consequences,” he explained, extending this to any professional field.

Self-censorship: The most sophisticated form

Another worrying area in the West is “indirect censorship or self-censorship” in which the person, on his or her own and without the intervention of censors, “understands that it’s better not to [speak out] because otherwise there will be consequences.”

Bazán identified these new forms of indirect censorship, which he characterized as the most sophisticated form of classic censorship, “through proxies, for example, or through online platforms that are forced to establish a content moderation policy that introduces prohibitive elements imposed by the state.” In these cases, “it’s not the state that censors, it’s the platform.”

The result, he explained, is that “the censored person will simply see that the message no longer appears because it has disappeared from the platform. And he may even receive a message stating that he will not be able to post anything on social media for x amount of time.”

In many cases, he added, “fact-checkers, who are often ideologically biased NGOs [nongovernmental organizations], simply try to censor certain types of messages that go against a particular way of understanding society.”

‘An invisible wall’ and restrictive European rules

Bazán pointed out that “dissent is avoided” and that Christians “can see how they find themselves up against a kind of invisible wall, which no one denounces. In many cases, the wall isn’t even established by the state but is rather a combination of state and non-state elements in which it is very difficult to determine who is ultimately creating this situation.”

This story was first published by ACI Prensa, CNA’s Spanish-language news partner. It has been translated and adapted by CNA.